The Cardinals need to reclaim spirit of '64 to heal St Louis' racial tensions

In the wake of the Michael Brown shooting white and black Cards fans have clashed over the case – the team must try to bring them back together as it did in the civil rights era

Before the St Louis Cardinals’ first home playoff game on Monday, the team reunited its World Series-clinching battery from fifty Octobers ago – Bob Gibson and Tim McCarver – for the ceremonial first pitch.

McCarver and Gibson were there to evoke the Cardinals’ long tradition of post season glory. But they might also have summoned forth other memories from 1964 – ones that would stand in stark contrast to the scene that unfolded outside Busch Stadium before the game.

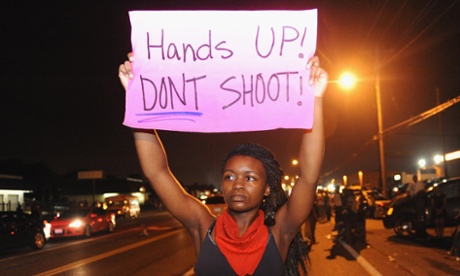

There – not far from a bronze statue of Gibson himself – a crowd of African American protestors were chanting for justice for Michael Brown, the unarmed black teen killed two months ago in the St Louis suburb of Ferguson. The demonstrators got an ugly reception from some of the Cards’ diehard fans, to the embarrassment of the team and the city.

Those very same fans may later have stood in tribute to McCarver and Gibson, Cardinal heroes who embody the racial attitudes of a more hopeful era. As David Halberstam ably documented in his book October 1964, the Cardinals’ success in the 1960s owed much to their progressive embrace of racial diversity.

McCarver, a son of the Jim Crow South, had never met self-assured black men like the ones he encountered on the St Louis roster in the early 1960s. Here was Gibson, one of the most forceful competitors of his era; Bill White, later the first African American league president in major sports; and the fearless Curt Flood, whose campaign against MLB’s reserve clause would eventually liberate professional athletes in all sports from (to borrow Flood’s phrase) “well-paid slavery.”

Those players—along with white Cardinal veterans like Stan Musial and Ken Boyer – taught the Memphis-bred McCarver one of the core values of what has come to be called “the Cardinal Way”. The young catcher learned to respect all his teammates – and opposing players, and everyone he met outside his baseball life – equally.

White and black Cardinal players of the 1960s didn’t merely tolerate each other. They enjoyed each other’s company. They played interracial hands of bridge, hosted interracial dinner parties, and sent their kids to interracial schools. Cardinal owner Gussie Busch bought his own motel in St Petersburg so that his players and their families could occupy integrated lodgings in segregated Florida during spring training.

The Cardinals achieved this harmony in the midst of a bloody era that witnessed the Freedom Rides, the Birmingham church bombings, and the march on Selma. During the same championship season of ’64 that the Cardinals proudly remembered on Monday night, three civil rights workers – young men only a couple of years older than Michael Brown – were murdered by the KKK in Neshoba County, Mississippi.

That was also the summer that LBJ signed the Civil Rights Act into law. St Louis had by then already shed much of the racial baggage that came with Missouri’s legacy as a slave-owning “border state” in the Civil War. The city witnessed sit-ins at segreated lunch counters as early as 1947, more than a decade before similar protests in the Deep South. The Board of Aldermen passed an ordinance the following year integrating all public buildings, and formally outlawed segregation in all settings, public and private, in 1961.

They were small steps that only began to address St Louis’s racial challenges. But they were steps in a constructive direction – and consistent with the spirit the Cardinals exhibited on the field.

One wonders what McCarver, Gibson, their teammate Mike Shannon (now the Cardinals’ radio play-by-play man), and other members of the ’64 Cardinals made of the tense scene outside Busch Stadium on Monday night. And one worries about what might happen – in front of a national audience – if hostilities intensify during the National League Championship Series, which begins on Saturday night in St Louis.

Ferguson protesters have planned large demon-strations throughout the city this weekend, and those will surely be amplified by Wednesday’s fatal shooting in St Louis of another black suspect by an off-duty white policeman. A group of Cardinal fans are making things worse by attempting to bring the conflict inside the stadium. They’re planning to wear T-shirts and wristbands emblazoned with the team’s name and colors, plus the name “Darren Wilson” – the Ferguson officer who killed Michael Brown.

Perversely, the T-shirts bear the number 6 – the same number worn by the greatest Cardinal ever, Stan Musial.

Do those T-shirts represent the “Cardinal Way”? Surely the dignified Musial – who witnessed the ugliest forms of racism first-hand when Jackie Robinson broke baseball’s color line back in 1947 – wouldn’t think so. And neither do the Cardinals’ current executives, who issued a statement pleading for peace after the unseemly behavior they witnessed in front of their ballpark during the NLDS.

They can do more.

The Cardinals unite the city of St Louis as no other civic institution can. As the rest of the country has noted (with growing irritation), St Louisians take tremendous satisfaction in the success of our baseball team. Michael Brown was no exception; like almost every local kid, he identified as a proud member of Cardinal Nation. (The Cardinals hat he was wearing when he was shot rested atop his casket on the day of his funeral.) So, no doubt, do most of the officers who investigated Brown’s death, and who policed the demonstrations in the weeks that followed.

That’s why the Ferguson protestors chose to stage their demonstrations at Busch Stadium earlier this week – there’s no better place to get the whole city’s attention. And it’s why the Cardinals would be well-advised to take an emphatic stand against the bitterness that has spread from Ferguson to their front doorstep, and now threatens to come through their turnstiles.

If the organization does not get ahead of this curve, it runs the risk of an ugly clash that would turn a potentially joyous occasion into a disgraceful one.

The Cardinals can counteract that possibility by, first of all, demanding that fans leave their Ferguson-related T-shirts, wristbands, and banners outside the ballpark. Better yet, they can celebrate the example of interracial comity established by earlier generations of Cardinal players. Back when Gibson and McCarver played, the races were as divided as they are today, perhaps more so. But the Cardinals stood for something else – something better – both within their clubhouse and on the field.

So when, in the NLCS pregame ceremonies, the Cards honor the heroes of post-seasons past, they also can and should invoke the larger Spirit of ’64 that McCarver and Gibson – two lifelong friends, one white and one black – displayed on Monday night before NLDS Game 3.

It might take a strong gesture – like sending an interracial group of local Little Leaguers out to the Cardinals’ positions before the team takes the field, or inviting the award-winning, racially diverse Metropolitan Community Church of Greater St Louis Choir to sing “God Bless America” during the 7th inning stretch.

Direct appeals from today’s Cardinal players – a racially mixed lot that includes Anglos, Asians, African Americans, and Latinos – would not be unwelcome.

One way or another, the Cardinals need to push back against the attempts by a handful of St. Louisians to bring shame on their team and their city.

Larry Borowsky is a St. Louis native and founder of the Cardinals blog Viva El Birdos.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please leave your ideas